Curriculum

Overview of our curriculum

Overview of homework

Overview of PSHE (including RSHE)

Overview of Key Stage 4 Courses

Introduction to our curriculum policy

"Divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived.”

For most people, reading that short familiar phrase will have triggered dozens of thoughts, facts, and concepts. Without giving any other context, they are suddenly enmeshed in questions of absolute monarchs, international alliances, and the interplay between religion and power that ripple down from Tudor England all the way to the present day, exposed through Islamic fundamentalism, Brexit, and tabloid fascination with Will and Kate.

Knowing those things – and not just recalling the bald facts but deeply understanding them – gives those people an upper hand. It gives them the confidence to discuss a wide range of live topics with those around them and it gives them social status. It makes them part of the club that runs the world, and the inside track to change it.

Staff at Tanfield School want to pull down the barriers to joining that club, to help students from all backgrounds feel comfortable engaging with the complex world around them. We do this by promoting the benefits of a knowledge-rich curriculum.

Knowledge and skills

We believe that students need a knowledge-rich curriculum to ensure they have solid foundations across a range of subject areas. We feel that a structured, well-planned curriculum, which offers appropriate progression and builds on prior learning, is the best way to prepare students for success in public examinations and equip them for their future careers.

The focus on imparting knowledge does not mean that we dismiss the value of pupils acquiring skills. However, we recognise that pupils cannot be taught skills in a vacuum and benefit from expert, teacher-led instruction in order to acquire secure subject knowledge as a platform for their learning.

We value the contribution that research in the field of cognitive science brings to education. For example, as outlined in Daniel Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School, research has shown that a broad and significant knowledge base is an essential prerequisite for developing what is commonly known as skills. The majority of what we call ‘skills’ are actually many pieces of knowledge called upon in different ways. For example, the ‘skill’ of inference is to decipher a message that is not explicitly stated in the text or speech, and is hence best developed through expanding vocabulary, wider knowledge of culture as well as common idioms and phrases. Cognitive science also suggests that these ‘skills’ are domain specific – for example being creative in one arena or discipline requires being extremely knowledgeable in that domain, but that creativity can’t be easily transferred to another domain without significant knowledge in the new domain or subject.

At Tanfield, we want our pupils to create, infer, analyse, evaluate and synthesise; but in order for our pupils to be successful, they firstly need to know a lot. This is not just because we want them to be part of the club, but also because research shows us that having background knowledge helps us to be creative.

Tanfield School aims to provide high-quality education to all children, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds. It is widely recognised that pupils from deprived sectors of society are less likely to have had a knowledge-rich start to life and may already begin school at a disadvantage; our knowledge-rich approach is particularly valuable in helping to address this and close any gaps in attainment.

Examples of Detailed Knowledge Planning

At Tanfield, we believe that knowledge is power. We plan our curriculum so that lessons challenge students to apply their knowledge in new and difficult contexts. Knowledge enables them to unlock doors that may otherwise be closed to them. Here are some examples of how our subject leaders organise this.

The evidence for knowledge over skills

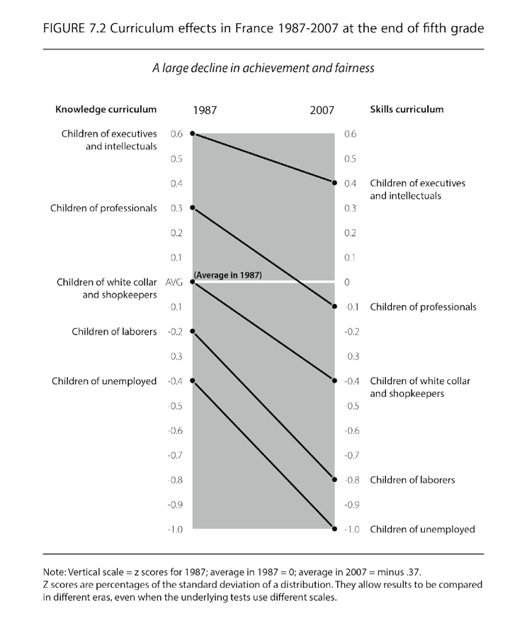

The graph above was taken out of E.D. Hirsch’s book ‘Why Knowledge Matters.’

How we develop the curriculum

At Tanfield we define ‘curriculum’ as what is to be learnt. The full implications of this are that

teachers are professionals and are hence responsible for debating and challenging what is learnt – and

in what order it is learnt. To ensure that the curriculum is not limited to the narrow view handed down

by the National Curriculum or by the specifications of GCSE qualifications, we start by asking our

subject specialists:

What are pupils entitled to know in your subject?

Which sequence of knowledge best supports pupils’ acquisition of that knowledge?

We have avoided extending our Key Stage 4 into Year 9, because we believe that even in subjects that

pupils do not take for GCSE, there is knowledge they are entitled to, and that three years is the

absolute minimum entitlement in these subjects.

The second question about sequencing, we frame around filling in the blanks of “We teach __________ in

Year ____ so that pupils can access _______ in Year ___” We deliberately start with a focus on Key Stage

3 so that the starting point is not the exam specifications – after all, the specifications are a sample

from the subject and limited in themselves. So reducing the subject to the exam specification threatens

to really impoverish the curriculum.

We insist that each department are members of and engage with the subject-specific community outside of the school, and that we actively seek out other schools and trusts that have an explicit knowledge-based outlook. Asking subject leaders to explain their decisions about sequencing of the curriculum alongside other subject specialists is a route to greater degrees of challenge to ensure an established curriculum.

Almost all continued professional development and learning (CPDL) time is focused on subject-specific considerations, so that even when this does reference pedagogy, it inevitably comes back to questions of curriculum. We ensure that all of our colleagues access great CPDL and we take seriously our responsibility to develop teachers to be the best that they can. Our CPDL programme is subject-specific, regular, and focused on ensuring colleagues take advantage of the autonomy they are granted within the vision of the school.

How we monitor the curriculum

The curriculum is a key priority at Tanfield and the focus of our development. It is under review including at line management meetings that occur every two weeks. Explicit curriculum review meetings with senior leaders and the headteacher take as significant a place in the school calendar as ‘standards review meetings’ that follow data collections.

Engaging parents with the curriculum

Engaging parents in the learning process is a key part of our strategy for successful curriculum implementation, with the expectation that knowledge will be reinforced at home. Parents attend workshops to explain our methods and are issued with curriculum maps and topic packs to enable them to support their children. To establish core knowledge, we know that memory is the most important process to harness. Therefore, all homework tasks are carefully planned to consolidate the learning done in the school day, through the process of low stakes testing.

Our commitment to developing sustained capacity for hard work means that every day students are required to revisit prior learning in order to interrupt the forgetting of knowledge. This approach means that a culture of revision is at the heart of students’ everyday practice. We teach core knowledge alongside teaching students how to revise from day one. There are daily routines that are established to ensure students practise the processes that need to become automatic. For example, at the start of lessons, every student completes a low-stakes quiz on their core knowledge. The sequencing of this is critical, as memorising core knowledge needs to be folded into practising more advanced skills.

If you require any further information about our curriculum please contact Joy Drake by telephone on 01207 232 881 or by email at jdrake@tanfieldschool.co.uk